Sumit Roy

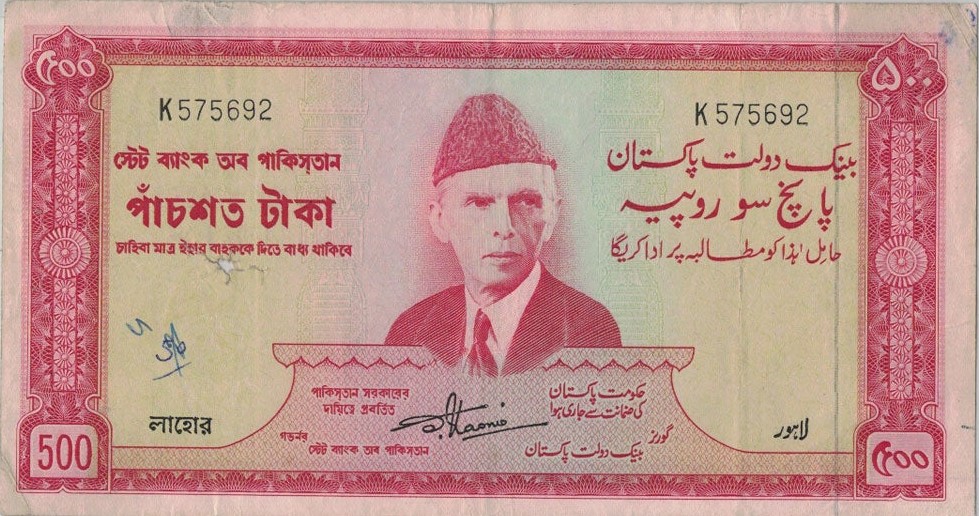

On 8th June 1971, the Pakistan government promulgated Martial Law Regulation No. 81 that demonetized two categories of currency notes: (a) all currency notes stamped with “Joy Bangla”, “Bangla Desh”, “Dhaka” or any term that hinted at secession or independence of East Pakistan & (b) all currency notes of denominations 100 and 500, irrespective of whether they were stamped with anything or not.[1] The demonetization was put into place with immediate effect.

The pro-liberation East Pakistan rebels or Muktijoddhas as they came to be known, had apparently looted several banks around March-April in a bid to finance their armed struggle. According to reports, they had used the money to buy arms and ammunition across the border in India.[2] At the same time they had also stamped the bank notes with “Joy Bangla” or “Bangla Desh”, not only as a proclamation of Bangladesh’s sovereignty from Pakistan but also to spread the message of ‘liberation’ quickly among the masses.[3] The Pakistani establishment rationalized the demonetization order as a means of strangulating the rebels’ finances as well as halting the inflation.

A few days before the demonetization order, President Yahya Khan had claimed that 100 million Pakistani rupees had been looted by the rebels.[4] According to a report in the New York Times, the Muktijoddhas had looted 10% of the money in circulation.[5] The Times of London reported that the rebel guerillas took approximately 30 million British pounds worth of looted Pakistani currency across the border and converted them to British pound sterling in the forex black market.[6] It was believed that speculators were holding huge quantities of Pakistani rupees in Afghanisthan, Hong Kong and India.[7]

Along with the demonetization order, the government also announced to the public that any one holding the demonetized currency notes must return them to any state owned bank within three days.[8] As people rushed to the banks with 100 and 500 rupee notes, they were handed receipts instead of new bank notes.[9] Rumours were abuzz that if serial numbers of the deposited bank notes matched with those looted by the rebels, the depositor would be arrested on charges of sedition.[10] For the Hindus, the fear was real and for obvious reasons it was next to impossible for any Hindu in possession of such notes to report them to the banks.

What was it like for a Hindu in East Pakistan in the second week of June, 1971? The Operation Searchlight had concluded a couple of weeks back on 25th May 1971, with the Pakistan Armed Forces taking control of the entire province, establishing themselves firmly in all the district and sub-divisional headquarters. In the process, they had liquidated hundreds of thousands of unarmed Hindus, whom they believed to be anti-state elements on the account of their purported association with India. By the end of May around 4 million refugees, overwhelmingly Hindus, had taken shelter in India.[11] Now, the Pakistan Armed Forces resorted to ‘search-and-destroy’ missions where Hindu villages and neighbourhoods were destroyed as a punitive measure against the ‘collective responsibility’ they owed for reportedly sheltering pro-liberation rebels.[12] Hindu bank accounts were frozen.[13] Cash rewards were announced for sharing the whereabouts of the Hindus.[14] Hindu houses and businesses were marked with ‘H’ in yellow.[15]

In the face of such awesome persecution, reporting one’s identity in a state owned institution, that too in possession of bank notes that imply sedition, was next to suicide. Naturally, none of the surviving Hindus in East Pakistan showed up. Those who had fled to India, didn’t risk going back either. However, they were relieved when the Bangladesh Betar, the clandestine radio station operated by the Provisional Government of Bangladesh, repeatedly announced that the independent Bangladesh government would reinstate the demonetized currency notes.[16]

The State Bank of Pakistan had issued new bank notes a few weeks after the demonetization order and they soon went into circulation.[17] After the fall of the Pakistani regime in Dhaka on 16th December 1971, the new bank notes still continued to be used as the medium of transaction. The central regulatory bank of Bangladesh, the Bangladesh Bank was not born yet. Almost a year later, a presidential order namely The Bangladesh Bank Order, 1972, passed on 31st October 1972, led to its formation.[18] The Clause (24) of the order sanctioned the use of all the newly issued currency notes of Pakistan as legal tenders in Bangladesh till further notice and the Clause (25), explicitly forbade the use of 100 and 500 rupee notes of Pakistan that were issue before 8th June 1971, in effect upholding Yahya’s demonetization order.[19]

The Bangladesh government’s decision was in direct contradiction to the repeated statements made by the Provisional Government of Bangladesh through Bangladesh Betar during the Liberation War. The Bengali Hindu refugees who returned back to their newly liberated country were shocked by this decision. Not only had they lost their kith and kin, homes and hearth, and all the material possession, they also lost the meagre savings in the form of 500 rupee notes that they could salvage before fleeing for their lives to India.

Dr. Kalidas Baidya, in his semi-autobiographical memoir ‘Bangalir Muktijuddhe Antaraler Sheikh Mujib’ has explained why the Hindus were exclusively impacted by this. He argued that the common Muslims could still get the demonetized notes in their possession exchanged at the banks, but the Hindus did have that opportunity. He has further argued that in spite of having a full understanding of the situation Prime Minister Sheikh Mujibur Rahman upheld Yahya’s decision, perhaps constrained by the declaration of Bangladesh as a successor state of Pakistan.[20] Even then, as any rational mind would expect, he as the Prime Minister of Bangladesh could surely have allowed for a window to exchange the demonetized bank notes with newly issued bank notes from Bangladesh Bank.

Given the scarcity of data points that are publicly available half a century after the event, an estimation of the loss is certainly difficult if not impossible, but certainly worth a try. New York Times had reported that the 100 and 500 rupees in circulation at the time represented approximately 60% of the valuation of Pakistan’s total circulating currency.[21] According to the data from the Economic Survey and Annual Reports of the State Bank of Pakistan, the monetary base in 1971 amounted to 8.156 billion rupees, 60% of which is 4.894 billion.[22] If the Hindus of East Pakistan, who constituted at least 7.5% of the population of the whole country, are considered to have possessed a proportionate amount of the total currency in circulation, the total monetary loss of Hindus through demonetization amounted to 367 million Pakistani rupees, a colossal loss that neither Pakistan or Bangladesh cared about.

[1] Symes, Peter (2000). “The Pakistan Overprints of Bangladesh”. International Bank Note Society Journal. Volume 39. Issue 3.

[2] Qureshi, Khalida (1971). “An Overview of the East Pakistan Situation”. Pakistan Horizon. Volume 24. Issue 3. Pakistan Institute of International Affairs. p. 46.

[3] Symes, Peter (2000). “The Pakistan Overprints of Bangladesh”. International Bank Note Society Journal. Volume 39. Issue 3.

[4] Pakistan Recalls Bills Of 500 and 100 Rupees (8 Jun 1971). New York Times.

[5] Rush on Banks in E. Pakistan (9 Jun 1971). Palm Beach Post.

[6] The Times. London. 19 July 1971

[7] Rush on Banks in E. Pakistan (9 Jun 1971). Palm Beach Post.

[8] Rush on Banks in E. Pakistan (9 Jun 1971). Palm Beach Post.

[9] Moinuddin, Faruq (17 Dec 2016). “নোট বাতিলের ক্রিয়া-প্রতিক্রিয়া (Note Batiler Kriya-Pratikriya)”. Prothom Alo. Dhaka.

[10] Moinuddin, Faruq (17 Dec 2016). “নোট বাতিলের ক্রিয়া-প্রতিক্রিয়া (Note Batiler Kriya-Pratikriya)”. Prothom Alo. Dhaka.

[11] Kennedy, E. M. (1971). “Crisis In South Asia”. Committee On The Judiciary,

U.S. Senate, Subcommittee To Investigate Problems Connected With

Refugees And Escapees. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 6

[12] Kennedy, E. M. (1971). “Crisis In South Asia”. Committee On The Judiciary,

U.S. Senate, Subcommittee To Investigate Problems Connected With

Refugees And Escapees. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 49.

[13] Schanberg, Sydney H. (4 Jul 1971). “Hindus Are Targets of Army Terror in an East Pakistani Town”. New York Times.

[14] Kennedy, E. M. (1971). “Crisis In South Asia”. Committee On The Judiciary,

U.S. Senate, Subcommittee To Investigate Problems Connected With

Refugees And Escapees. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 48.

[15] Schanberg, Sydney H. (4 Jul 1971). “Hindus Are Targets of Army Terror in an East Pakistani Town”. New York Times.

[16] Baidya, Kalidas (2005). বাঙালির মুক্তিযুদ্ধে অন্তরলের শেখ মুজিব (Bangalir Muktijuddhe Antaraler Sheikh Mujib). pp. 313-314.

[17] Moinuddin, Faruq (17 Dec 2016). “নোট বাতিলের ক্রিয়া-প্রতিক্রিয়া (Note Batiler Kriya-Pratikriya)”. Prothom Alo. Dhaka.

[18] Bangladesh Bank. Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Bangladesh.

[19] Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs (31 Oct 1972). Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Bangladesh.

[20] Baidya, Kalidas (2005). বাঙালির মুক্তিযুদ্ধে অন্তরলের শেখ মুজিব (Bangalir Muktijuddhe Antaraler Sheikh Mujib). pp. 313-314.

[21] Rush on Banks in E. Pakistan (9 Jun 1971). Palm Beach Post.

[22] Chaudhary, M. Aslam; Khan, Aurangzaib (1997). “Volatility of Money and Monetary Policy in Pakistan”. Pakistan Economic and Social Review. Volume 35. Issue 2. University of the Punjab. p. 147.