Every civilisation negotiates power not only through politics and armies, but through time

itself—through calendars, festivals, and collective memory. Colonialism understood this well. It did not merely rule territory; it reorganised days, seasons, and celebrations. Against this backdrop, the contemporary debates around Tulsi Pūjan on 25 December and Kalpataru on 1 January are not trivial cultural arguments. They are echoes of a much older, deeper civilisational response—one that reached its most luminous expression in Paramahamsa Sri Ramakrishna. (From Christmas to Kalpataru)

A familiar Leftist question is repeatedly raised today: why is Tulsi Pūjan not observed according to lunar tithi? If Hindu worship follows the lunar calendar, why fix it to an English date like 25 December? The counter-question is equally simple and revealing: is Kalpataru Utsav a tithi-based observance? The question is not calendrical accuracy; it is discomfort. The discomfort arises because a Christian festival day has been passed—peacefully, without bloodshed, without erasure—by a Hindu spiritual assertion. That unsettles those who see culture only as a political zero-sum game.

To understand why this matters, one must return to history. From 25 December to 1 January, the Christian calendar had long been saturated with festivals, carnivals, and symbolism—Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, New Year celebrations—marked by cakes, pastries, Christmas trees, Santa Claus, and nativity tableaux. These were not confined to Europe; through colonial power, they spilled into colonised societies. Conversion was often not a matter of persuasion but of authority—carried out from the ruler’s chair, under the intimidating gaze of the empire.

India was an exception. Despite colonial dominance, its Sanatani society continuously

experimented with ways to preserve, adapt, and reassert its religious and cultural life. The

answer was neither violent rejection nor submissive imitation. It was something subtler: civilisational transcendence.

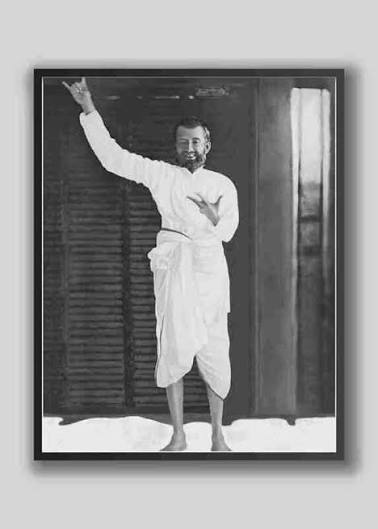

That transcendence reached a decisive moment on 1 January 1886, when Sri Ramakrishna became the Kalpataru—the wish-fulfilling divine tree. On that day, he blessed Bengalis and humanity at large with an awakening of consciousness. From then onward, the Christian calendar itself carried a Hindu spiritual milestone: Kalpataru Day. A date once meant solely for colonial festivity was quietly, bloodlessly transformed into a day of uncaused grace. This was not confrontation; it was absorption. Not resistance, but a spiritual revolution.

The symbolism is profound. The Christian New Year’s Day—part of the winter festival season beginning with Christmas—was “bowled out,” as it were, by a sacred Hindu touch. No riots, no coercion, no counter-carnival—only a silent assertion that consciousness, not power,

determines meaning. As time passes, the magnitude of this victory becomes clearer.

This was no accident of history. In 1835, Thomas Macaulay sought to reshape India through an education policy designed to sever indigenous culture from its roots. Yet, almost poetically, the response arrived the very next year. On 18 February 1836, on Phalguna Shukla Dwitiya, Sri Ramakrishna was born. As the old saying goes, “The one destined to destroy you is growing up elsewhere.” He appeared not as a political rebel, but as a force that would dismantle colonialism at the level of the mind.

His life itself was steeped in continuity. Named Gadadhar after his father Khudiram

Chattopadhyay received a divine vision of Vishnu at Gaya, Sri Ramakrishna’s birth was

accompanied by another mystical event: a radiant light from Shiva at the Yogeshwar temple in Kamarpukur entering his mother Chandramani Devi. Though astrologically named Shambhu Chandra, he became known as Gadadhar, later lovingly shortened to Gadai.

His family embodied a centuries-old Rama-centric devotion. His grandfather Manikram, his father Khudiram, uncles, aunts, siblings, cousins—names like Ramkumar, Rameshwar,

Nidhiram, Kanai Ram, Ramlila, Ramtarak, Ramchand, Raghav, Ramratan—formed a living genealogy of faith. Khudiram himself, displaced by a zamindar’s oppression, lived in

Kamarpukur sustained by devotion to Raghubir alone. Villagers revered him like a sage; shopkeepers stood up when he passed, and bathing ghats were cleared in his honour. This was the soil from which Sri Ramakrishna arose.

Seen in this light, today’s triphala of observances—Dhuni Dibas or the Day of Renunciation (24 December), Tulsi Pūjan Dibas (25 December), and Kalpataru Dibas (1 January)—is not a political provocation. It is a civilisational statement. It declares that Hindu society does not need permission from the colonial calendar, nor does it need to abandon it. It can inhabit it, sanctify it, and transcend it. (From Christmas to Kalpataru)

Those who reduce everything to politics fail to grasp this deeper rhythm. Culture is not merely resistance; it is continuity with creative confidence. From 24 December to 1 January unfolds what may be called a season of the Hindu trident—silent, bloodless, and luminous. In that silence lies the true strength of Sri Ramakrishna’s legacy: not the negation of the other, but the fearless assertion of one’s own awakened self.

Also Read : Selective Silence: Violence, Videos and Vigilance in Bangladesh

Sri Sri Ramakrishna Lilaprasanga – Swami Saradananda

Aritra Ghosh Dastidar